A stunningly strong 12 months for the tanker shipping industry is now being replaced by lower freight rates, as lower oil production and demand sets in across the globe, writes BIMCO CEO, Peter Sand in an article published on their website.

Only China bucks this trend with record-high crude oil imports, benefiting from the low oil price. Given the global recession and lower transport demand, however, the tanker industry is set for some challenging months.

Demand Drivers And Freight Rates

- Crude oil and oil products were among the commodities most affected, most quickly, by the lockdowns around the world. In its latest forecast, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that global oil demand in 2020 will fall by 8.1 million barrels per day (bpd).

- Though revised slightly upwards from its May report, when it forecast a drop of 8.3m bpd, the downside risks weigh on the forecast as the coronavirus continues to spread.

- The drop wipes out six years of demand growth, with 2021 unlikely to see a return to 2019 levels.

Tanker Freight Rates Fall

The tanker industry experienced a boost immediately after the start of the COVID-19 crisis, because of the lower oil price and higher exports from major producers. In the long run, however, the lower aviation and transport demand, and fundamentally lower oil consumption, will hurt the industry for at least 15 months.

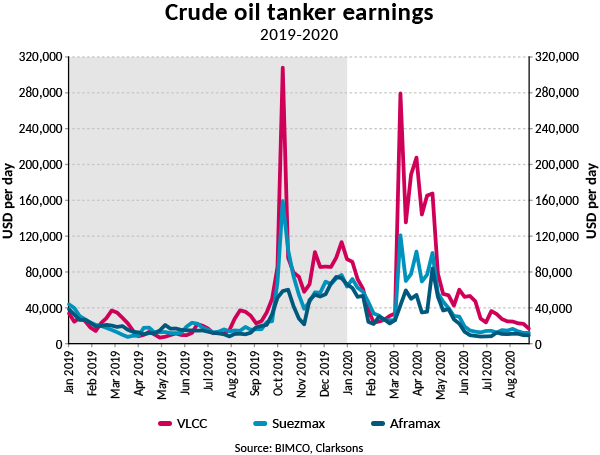

- Already, tanker freight rates have fallen from the highs they reached when the market peaked in April, with all crude oil tankers seeing earnings beneath their daily break-even levels.

- On 28 August, Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) earnings averaged USD 16,949 per day, indicating a loss of around USD 7,000 every day.

- At USD 11,949 per day, Suezmax earnings are also around USD 8,000 below breakeven, and Aframaxes can expect to lose USD 7,700 per day, with earnings averaging USD 9,322 per day.

- Oil product tanker earnings have fared less well, with the largest LR2 tankers earning USD 18,785 per day on 28 August.

- Handysize rates have recovered from their low of just USD 1,974 per day on 21 August, to stand at USD 5,601 a week later.

Time Charter Rates Fall

Time charter rates for tanker ships have also fallen.

- At the height of the oil price war, a one-year time charter for a VLCC would cost USD 80,000 per day; by 28 August, this had fallen to USD 36,000.

- A similar decline has occurred for LR2s, which, on 28 August, stood at USD 20,500 per day, down from USD 40,000 in late April.

Oil Imports Increase

Despite lower oil demand because of the public health measures, many countries saw imports rising year on year in the second quarter, as they sought to cash in on the cheap oil.

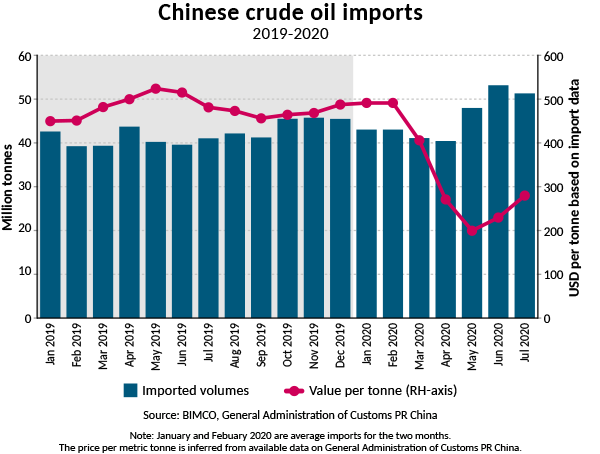

- China recorded its highest crude oil imports in May (48.0m tonnes), only for that record to be broken again in June, when imports totalled 53.1m tonnes.

- In July, China again imported more than 50m tonnes of crude oil (51.3m tonnes).

Between April and July this year, Chinese crude oil imports grew by 17.2% on last year, necessitating an additional 94 VLCC loads (300,000 tonnes) compared with the same period the year before.

Illustrating the falling price, despite the full-year 12.1% increase in volume terms, Chinese crude oil imports have dropped in value by 23.7%.

The high crude oil imports into China have again caused delays at ports, driving up the inefficiency of the fleet and lowering the number of ships that would otherwise be available – and, in that way, supporting freight rates.

Though Chinese demand for crude oil and oil products has risen from the low point in February, much of this extra crude oil is going straight into storage. This is either directly, as crude, or after having been processed.

In fact, crude processing reached its highest ever level in China in July, at 59.6m tonnes, with accumulated year on year volumes up 2.3% in the first seven months of the year.

Though internal demand has recovered in China, international demand has fallen, with exports down to 3.2m tonnes this July compared with 5.5m tonnes last year. Most of these exports went to short-haul destinations.

The easing of lockdown measures has sounded the starting gun for demand recovering, but the EIA and others are still forecasting lower demand in 2021 than in 2019, so major oil producers are having to find a balance between increasing production and slowly increasing demand.

Oil Production Cuts

- The OPEC+ alliance, which includes the OPEC countries as well as ten other oil producing nations, the largest of which is Russia, has already begun reducing its production cuts, increasing its output by 2m bpd to 7.7m bpd, from 9.7m bpd immediately after the oil price war.

- Elsewhere in the world, however, the still-low oil price is hindering some production from being restored. In the US, weekly crude oil production is still reduced from its high point in March (13.1m bpd), standing at 10.7m bpd.

Oil Products Demand Low

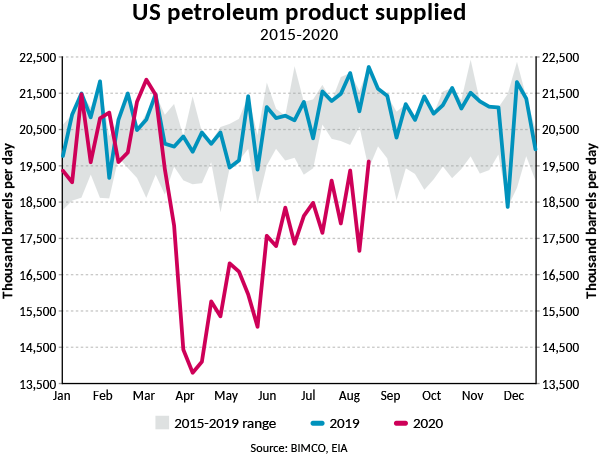

Like crude oil production, product supplied in the US remains below last year’s level, though up from the lows reached at the height of the lockdowns. However, as evidenced by flight passenger numbers in the US still being down considerably, demand for oil products still has a way to go. By 7 August, the US was supplying 19.4m bpd of oil products, the highest level since 20 March, but still 2.7m bpd (-4.1%) less than in the corresponding week last year.

The US is set to consider tightening sanctions on Venezuela at the end of October. This would aim to put a stop to the limited activity that is still happening, primarily with European and Asian buyers. Tensions have also been on the rise in the Middle East Gulf after US seizures of Iranian oil that was headed to Venezuela – which has also brought an increased focused on ships turning off their AIS locators when loading fuel in Iran, as well as ship-to-ship transfers.

Fleet News

- In contrast to the other major shipping sectors, the crude oil tanker sector has seen very little demolition in the first six months of the year.

- In fact, only seven crude oil tankers were demolished in the first eight months of 2020, totalling 681,832 dead weight tonnes (DWT).

- Year to date, no VLCCs have been demolished, while 26 were delivered, resulting in the VLCC fleet growing by 7.9m DWT.

- This is on top of the 68 VLCCs delivered in 2019, which led to the VLCC fleet growing by 8.6%.

- The last VLCC to be demolished was in June 2019, with only four having been demolished since October 2018.

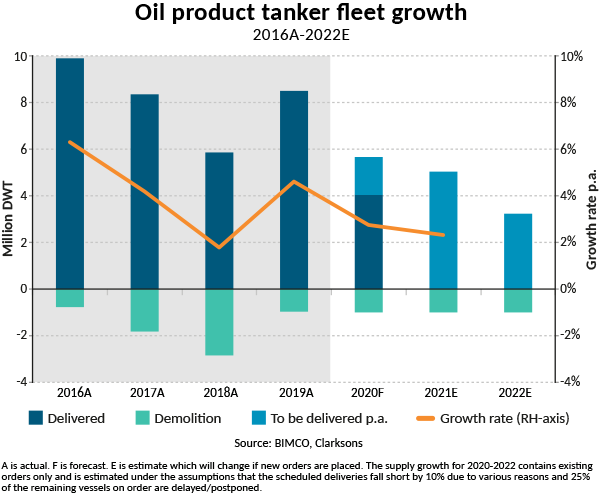

BIMCO expects demolition activity to rise as freight rates and actual demand for tanker shipping falls, with total crude oil demolition coming to 7.5m DWT in the full year and 1m DWT of product tankers being demolished.

So far this year, 547,334 DWT of oil-product tankers have been removed.

Over the full year, BIMCO expects that the oil product tanker fleet will grow by 2.7% and the crude oil tanker fleet by 2.4%.

This represents a marked slowdown from last year, when they grew by 4.6% and 6.2% respectively.

Total tanker deliveries have totalled 16.2m DWT so far this year, a 43.9% drop from last year.

Fleet Growth Slow Down To Continue

This slowdown in fleet growth will continue in the coming years, as the pandemic has lowered contracting activity.

- Contracting for crude oil tankers has fallen by 37.9% so far this year compared with last.

- At 4.1m DWT, product tankers is the only segment in which there have been more new orders in the first eight months of this year than the same period of last year (+31.9%).

- Ten of these orders are for a series of 50,000 MR tankers placed by Bahri.

The lower contracting activity fits with the poorer outlook, which is also reflected in the value of second-hand tankers.

- Prices for 10-year-old VLCCs and LR2s both fell by 19.2% and 18.4% respectively from the start of the year to late-August.

- A new VLCC is worth 7.5% less now than at the start of the year, and the value of an

- LR2 has fallen by 1.7% – drops of USD 7.35m and USD 0.86m respectively.

Market Outlook

Despite tensions between the US and China ratcheting up in previous months, there was progress made on the Phase One trade agreement, with record-high US crude oil exports to China in May, when 5.1m tonnes was exported. China remained the largest destination for US seaborne crude oil exports in June, even as exports halved. Whether or not China continues to make these higher purchases of US crude oil remains to be seen, with any that are made providing a good boost to the crude oil tanker shipping market, given the long sailing distance between the loading and discharging ports.

Despite the strong purchases in May and June, however, China remains far behind on its commitments under the Phase One agreement. Because the agreement is made in value rather than volume, the recent drop in oil price has made it even harder to achieve than previously, although it would provide an even bigger increase in demand for shipping were China to meet its commitments. A six-month review of the deal, originally scheduled for mid-August, has been postponed, with no new date set, highlighting the tensions between the two countries.

The question of when demand will return to pre-pandemic levels remains clouded in uncertainty as the virus continues to spread. Travel restrictions remain complicated and demand for global travel is still abated. Land-based transportation has had a stronger recovery than air transport, but it remains lower than this time last year.

The EIA doesn’t expect global oil demand to return to pre-pandemic levels in 2021; instead, it sees demand rising to 100.17m bpd in 2021 (in 2019 it was 101.25m bpd). As it looks now, 2022 seems to be the year in which volumes will have recovered.

The loss of several years’ growth in global demand for oil – and, therefore, for tanker shipping – will lead to a worsening of the fundamental balance in the market. Though fleet growth will be lower, as a result of the drop in contracting during the pandemic and the poorer outlook in the coming years, the fleet will continue to grow year on year.

For the remainder of this year, the tanker shipping industry will find itself paying for the highs it reached in the second quarter. The higher demand for shipping at the time was not because of higher immediate consumption, but because of future demand being brought forward as importing refiners sought to benefit from the lower price.

Did you subscribe to our daily newsletter?

It’s Free! Click here to Subscribe!

Source: BIMCO