- The once attractive VLOCs are phased out due to safety concerns.

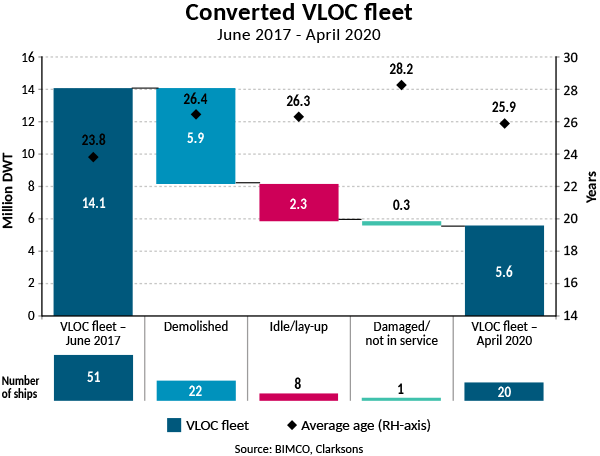

- 43% of the VLOC fleet has been sent to the scrapyards.

- 18% of the fleet is idled or damaged.

- VLOCs were converted from single-hull VLCC towards the end of 2000 as an innovative result of the dry bulk supercycle.

- The maintenance and repair costs are significantly higher than the younger tonnage.

- Conversion from the tanker to dry bulker came at an estimated price of USD 12-15m.

According to an article published in BIMCO and authored by Peter Sand, since June 2017, 43% of the VLOC fleet has been sent to the scrapyards, while 18% of the fleet is idled or damaged.

Safety of VLOCs

“The tragic Stellar Daisy accident brought the safety aspect of VLOCs into question. Now, three years on, three out of five VLOCs are no longer in operation as their long-term charters have now expired. Going forward, the obsolete VLOCs will be phased out of the market and replaced with technologically superior and more reliable ships,” says BIMCO’s Chief Shipping Analyst, Peter Sand.

The VLOCs were converted from single-hull Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC) towards the end of 2000 as an innovative result of the dry bulk supercycle and the IMO regulation which mandated that all single-hull tankers should be phased out by 2010. With cheap and obsolete tanker tonnage in the market, investors eyed an opportunity to convert the ships into VLOCs and deploy them on long-term contracts of affreightment, often with a duration of 10 years.

Is it wise to keep the old VLOC tonnage afloat?

In June 2017, BIMCO analyzed the VLOC fleet which at the time consisted of 51 ships with an average age of 23.8 years, not far from the average demolition age of 24.2 years. Back then, we argued that the ships on long-term contracts still made solid economic sense, given a second-hand price equal to the scrap value and stable earnings.

Arguably, the maintenance and repair costs are significantly higher than younger tonnage, but the statement from 2017 still holds true, granted the condition that the ships have employment under long-term contracts. Once the VLOCs no longer have to fulfill obligations under long-term contracts, the economic incentive to keep the ships afloat evaporates.

Solid return on investment

At face value, during their time as ore carriers, these ships have provided a solid return on investment, even when accounting for higher maintenance costs. Although the conversion from the tanker to dry bulker came at an estimated price of USD 12-15m, plus the cost of the actual ship, the freight revenue from the long-term contracts for carrying ore from Brazil to China have exceeded the cost by a fair margin.

Since the last analysis, the fleet has undergone a massive trimming with 28 ships remaining in the fleet, eight of which are lying idle in Labuan, a dedicated lay-up site. Since June 2017, 22 ships have been scrapped while one is damaged and not in service. Therefore, it seems likely that converted VLOCs will soon be a memory of the past.

Converted VLOCs are phased out for other options

The investment strategy of converting cheap tanker tonnage to dry bulk carriers seems unlikely to be replicated any time soon. With economic growth and prosperity comes opportunities. The VLOCs were acquired and contracted for conversion during the dry bulk bull run in 2007-2008, but many of the conversions were only complete after the financial crisis put an end to the bull market.

The ships entered a market, which never recovered to previous highs, but nonetheless remained a profitable one in the initial years. In 2009 and 2010, the Baltic dry index (BDI) averaged 2,616 and 2,758 index points respectively, well below the 6,390 index points seen in 2008, but a substantial margin above the averages from 2011-2019, which never exceeded 1,600 index points.

Approaching demolition age

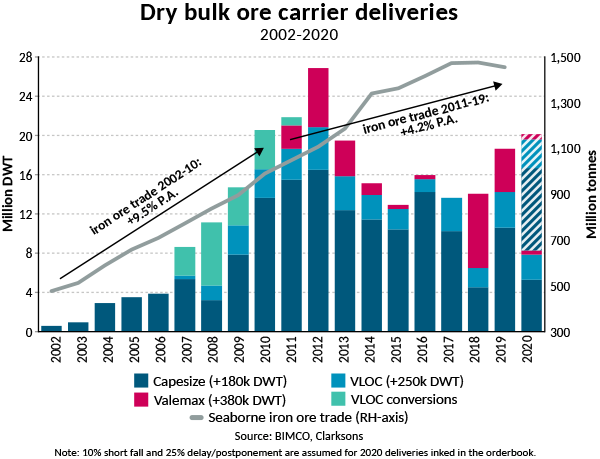

Many of the ships are approaching the average age of demolition, and these ships are set to be phased out as soon as the long-term contracts under which they are employed expire. However, new VLOCs and even larger ships, such as the Valemaxes, have already been supplied to the market. For this reason, the scrapping of converted VLOCs will not create a shortage of tonnage in the market.

Perhaps even the contrary holds true. From June 2017 to April 2020, the Capesize (+100k DWT) fleet grew by 29.6m DWT (9.2%). From 2017 to 2019, seaborne trade of iron ore declined by 17m tonnes (-1.2%)

“A shortage of tonnage will not arise because the converted VLOCs are now phased out. New and even larger ships have already been delivered to the dry bulk market, more than covering the transportation needs,“ Sand says.

Did you subscribe to our daily newsletter?

It’s Free! Click here to Subscribe!

Source: BIMCO