A Centre for Maritime Strategy news source is talked about in the book Securing Maritime Data: The Battle Against China’s LOGINK in U.S. and European Ports.

Securing Maritime Data from Communist China Act

On March 22, 2023, Senator Tom Cotton and Congresswoman Michelle Steel introduced the “Securing Maritime Data from Communist China Act,” aiming to ban the Chinese state-owned digital logistics platform LOGINK from use in domestic ports. This act would also require the U.S. President to negotiate termination of LOGINK’s use in allied ports. Only six days later, another bipartisan act known as the “Ocean Shipping Reform Implementation Act” was introduced. If signed into law, it would also prohibit U.S. ports from using LOGINK.

LOGINK is a unified digital logistics and trade platform administered by China’s Ministry of Transport. Initially developed in 2007 as a provincial initiative, it expanded regionally in 2010. Four years later, it became a global platform. Today, China continues to encourage entities like ports, freight carriers, and others to adopt LOGINK by providing it for free. The platform aggregates data from over 450,000 users in China, five million trucks, over 200 logistics warehouses worldwide, and dozens of ports in China and abroad, in addition to several other databases. With all this data, the platform “provides users with a one-stop shop for logistics data management and shipment tracking.” Due to the newness of logistics management platforms, China’s effort to obtain a first-mover advantage is significant. It could allow China to set the rules of the game.

Among the key risks involved are the unfair commercial advantage that Chinese companies may obtain due to the informational edge and the possible manipulation of LOGINK’s data for economic coercion purposes, disrupting, and even blocking the trade flow to certain countries. On top of these, LOGINK could conceal movements of the People’s Liberation Army and simultaneously provide China with information concerning U.S. military logistics. This would be significant since the U.S. Department of Defense uses civilian shipping and ports to move much of its materiel.

LOGINK’s European Presence and Expansion through Partnerships

While several U.S. bodies like the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission and public figures like Senator Cotton have expressed concerns about LOGINK and Chinese control of critical infrastructure, reactions in Europe have so far been more mild, even if Europe is facing an arguably bigger challenge on that front. For instance, Chinese companies have stakes in or operate 22 ports across Europe but only five in the U.S. The most recent high-profile investment was COSCO’s acquisition of a 24.9% in a container terminal at Germany’s largest Port of Hamburg. This was eventually green-lighted in May 2023, after six months of arguments within the German government, and against the advice of Germany’s intelligence service.

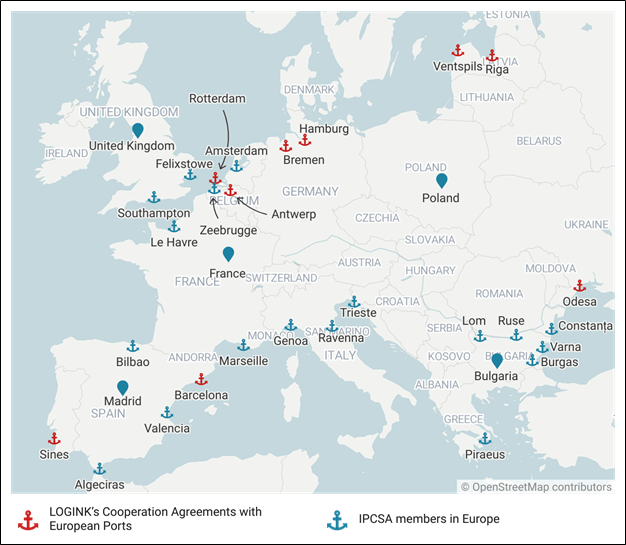

Figure 1. LOGINK’s Cooperation Agreements with European Ports and IPCSA Members in Europe

Meanwhile, LOGINK has agreements with at least 24 ports, freeports, and port operators outside of China. Of these, nine ports are located in Europe. None are located in the U.S. Paying attention only to LOGINK’s direct agreements with foreign ports, however, does not tell the whole story. It is also necessary to look at its rapidly growing repertoire of partnerships across the world. For example, LOGINK has a data-sharing arrangement with CargoSmart, a shipping management software provider, which is in turn owned by COSCO through its subsidiary Orient Overseas International Limited (OOIL). According to Chinese news sources, this partnership provided LOGINK with “access to data on live movements of more than 90 percent of the world’s container ships through CargoSmart.” A second partnership with CaiNiao, a global logistics giant with over 200 warehouses globally and a rapidly expanding European presence, has also given LOGINK an edge. Other relevant partnerships exist with Portbase in the Netherlands and Maqta in the UAE.

Lastly, the partnership with the International Port Community Systems Association (IPCSA) could be highly consequential. IPCSA recently launched the “Network of Trusted Networks,” a “project that will link some 70 ports and 10 airports, allowing them to share vessel and container status.” Successful integration with LOGINK could expand its reach dramatically. All these growth opportunities are being further exacerbated after LOGINK’s competitor TradeLens, a logistics platform launched by Maersk in 2018, announced it would close down in January 2023.

An Opportunity for US-EU Legislative Cooperation

Attitudes toward Chinese state-sponsored entities like LOGINK, the shipping company COSCO, and the crane manufacturer ZPMC are much more negative in the U.S. than in Europe, but new opportunities for transatlantic cooperation may be emerging. EU Parliamentarian Tom Berendsen has brought this issue to the Commission’s attention in recent months.

In November 2022, MP Berendsen argued that Chinese presence on data platforms of European ports was detrimental to European autonomy and asked what measures the Commission intended to take. The latter responded that it was aware of LOGINK and that the Commission would continue monitoring its use. The Commission added that the EU had set up Foreign Direct Investment screening measures, but it did not emphatically reject the adoption of LOGINK. A month later, MP Berendsen again asked about the measures the EU was taking to ensure its ports remained competitive without being dependent on foreign investment, after news emerged that the German government had accepted Chinese investment in the Port of Hamburg. Most recently, MP Berendsen questioned the Commission about the risks involved in using ZPMC cranes in European ports.

MP Berendsen’s awareness and concern could represent a starting point for new cooperative efforts between EU and U.S. legislators, who are similarly concerned by the impacts of LOGINK, COSCO, and ZPMC. Through the existing European Parliament Liaison Office in Washington D.C., legislators could start by sharing information and best practices, as well as coordinating their efforts. For example, EU legislators may want to use the two newly-introduced, U.S. bipartisan acts as blueprints for future European legislation.

Prohibit LOGINK? Not Appealing in the Short-Term, But Key to Avoiding Future Vulnerabilities

Restricting the use of LOGINK in European and U.S. ports may be costly and inefficient in the short term. And while choosing security over efficiency and cost savings may not be the most attractive option for some, the experience and lessons learned from Europe’s heavy dependency on Russian hydrocarbons should serve as a cautionary tale. A more delicate issue is the participation of European ports in IPCSA’s “Network of Trusted Networks.” As an international organization, IPCSA has a veneer of respectability, but European countries should act with caution. China is actively trying to set the agenda for logistics standards and the IPCSA, or other international organizations, may be inadvertently instrumentalized to help advance Beijing’s agenda.

Ultimately, the debate about LOGINK cannot be separated from Chinese investments in ports across the globe, provision of cranes, and broader Chinese efforts to become a logistics and transport superpower in the coming decades. Europe should address this conundrum now, or else it may find itself in a highly vulnerable position a few years down the road.

Did you subscribe to our daily newsletter?

It’s Free! Click here to Subscribe!

Source: Center for maritime strategy