Monitoring – Review – Verification Process (MRV) – (EU Regulation 2015/757)

Monitoring – Review – Verification Process (MRV) – (EU Regulation 2015/757)

Maritime transport is currently the only industry sector not addressed either through the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) or the EU’s Effort Sharing Decision on CO2, but represents 4% of total emissions and is recognized as the fastest growing sector in transportation. After consultation with all the stakeholders, it was agreed that there should be a staged approach and all companies should have an MRV for CO2 emissions by January 2018. It is expected that the introduction of an MRV will lead to a 2% reduction in CO2 emissions, which will relate to a saving of £1.2 Billion by 2030.

The MRV should cover all the relevant information that can provide an accurate assessment of the ship’s efficiency and the monitoring will focus on the calculated CO2 emissions as this is the most relevant Greenhouse Gas.

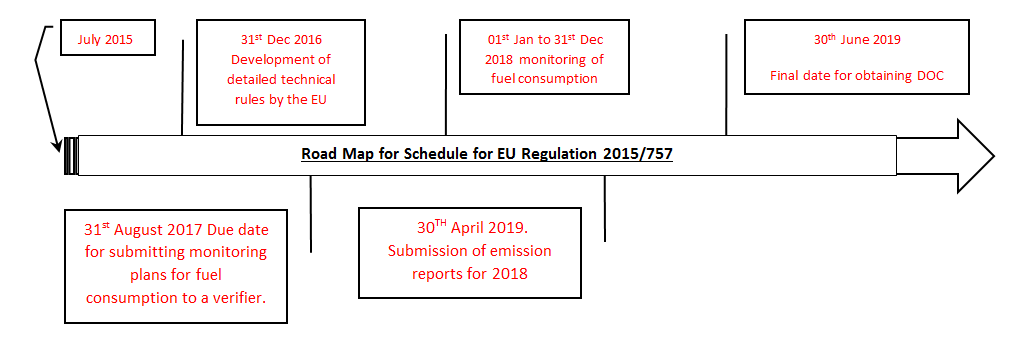

Shipping companies operating in the EU have until 2017 to prepare plans to monitor and report their carbon emissions. The reporting period itself starts from 1st January 2018, however, all companies need to submit a monitoring plan for each ship indicating the chosen method to monitor CO2 emissions and other relevant information by 31 August 2017.

In order to record this, there are various software based tools available in the market such as Mari-apps or VEEMS (Viswa Energy Efficiency monitoring System) which assist shipping companies in complying with the regulations. These software assists in capturing the data and then aggregating it for verification.

The CO2 emission reporting is required on an annual basis and the report should be performed by an ISO 17045 accredited verifier who should be independent and a competent legal entity. The verifier will issue the ship with a compliance certificate, valid for 18 months.

The shipping companies should be aware that there will be EU member state PSC inspections to check compliance with the MRV CO2 certificate. The penalty for noncompliance should be severe and dissuasive.

The ship operator will choose one of 4 monitoring methods

- Use of fuel bunker delivery notes

- Bunker fuel tank consumption

- Flow meters for equipment that emits gasses

- Direct emission measurement

The operator will then produce a ship specific monitoring plan, which should contain complete and transparent procedures about the monitoring methods for the ship concerned. The plan should include the following information:

- Name, IMO number, type of ship, Port of registry and name of the ship owner.

- The name of the company and address and contact details of DPA.

- A description of the sources of CO2 emissions on board the ship and the type of fuel used.

- A description of the procedures, systems, and responsibilities used to update the CO2 emission sources over the reporting period.

- A description of the procedures used to monitor the completeness of the list of voyages.

- A description of the procedures for monitoring the fuel consumption of the ship.

- Single emission factors used for each fuel type.

- A description of the procedures used for determining activity data per voyage.

- A description of the method used to determine surrogate data for closing data gaps.

- A revision records sheet.

The software such as Mari-apps or VEEMS can assist in MRV as it enables ship operators to monitor all vessel types within the fleet with a single integrated tool. It accommodates both manual and online data entry to monitor operational data per voyage, validate and generate reports for any time period on a per vessel basis.

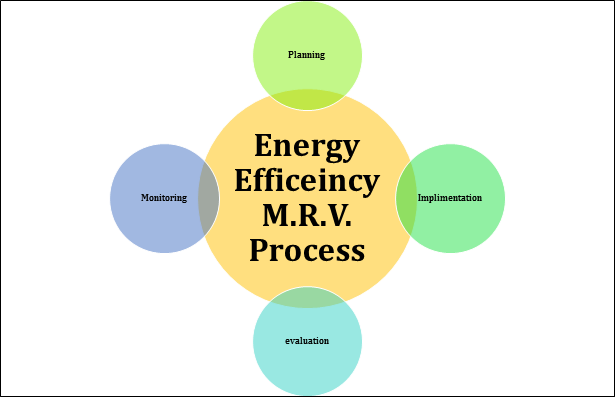

Below flow chart helps to illustrate the MRV process.

Planning

As part of each SEEMP, the shipowner is required to review current practices and energy usage onboard each ship with a view to determine any shortfalls or area of improvements for energy efficiency. Since this is a crucial first step towards developing an effective management plan, one should identify various aspects relating to:

- Ship-specific measures – which are – speed optimization, weather routing, hull maintenance, machinery operation.

- Company-specific measures – which are –

- Improved communication and interaction with other stakeholders, such as charterers, in order to assess feasibility of ‘just in time’ operation or traffic management services for availability of berth etc.

- Human resource development – Creating awareness and appropriate training for personnels is crucial in ensuring successful implementation of any measures.

- Goal setting or bench marking – This aspect is voluntary but serves as a means to ship owners in providing incentives for reducing energy consumption, both at ship level and at corporate level. This should not be subject to external inspections.

Implementation

Upon completion of the planning stage an implementation guide, depicting a system for how each energy improvement measure has to be implemented, needs to be put in place. The development of the system can be considered under the planning stage and it should layout the tasks required to achieve each measure along with who is incharge of completing them. The implementation procedures should comply with the implementation system developed and should be trackable with proper documentation and record-keeping, which should preferably be an electronic method for ease of access and audit.

Monitoring

The only way to assess whether the energy improvement measures are working is to quantitatively monitor each ship. A shipowner may already have an existing systems in place to measure this, still care should be taken to monitor by using established methods like international standard.

The SEEMP guidance (MEPC.213(63)) recommends one internationally established tool in particular which can be used for monitoring the “Energy Efficiency Operational Indicator (EEOI)”. This tool has been developed by the IMO to quantify the energy efficiency of a ship in terms of CO2 production per cargo tonne-nautical mile (g CO2 / t.nm). Its use and calculations are given in MEPC.1/Circ.684. In addition to it the tool suggests that, if appropriate, a Rolling Average Index of the EEOI may be used to monitor energy efficiency of the ship over time.

Self-evaluation and improvement

This is the final stage in the cycle and its the means by which each measure can be assessed and the results can be fed to the planning stage of the next improvement cycle. Self-evaluation and improvement phase not only identifies how effective each energy improvement measure is, but also determines if the process by which it had implemented and monitored the system was smooth and identify the areas of improvisation required. Each measure needs to be evaluated individually on a periodic basis and the results should be used to understand the level of improvements observed for each ship.

However before embarking on a Plan (implementation – Monitor – Evaluation cycle) we need to prepare the vessels by a process called GAP-ANALYSIS.

This can be done internally if the company has sufficient resources and skill for same or outsource to other leading classification societies and independent bodies which may do it for a fee.

A GAP-Analysis audit assesses the shipping company for energy efficiency MRV readiness. The audit identifies the gaps in processes & systems and identifies the areas of improvement. The benefit of this audit, if carried out properly, is to identify all compliance and process issues. This helps in fixing the needed corrections by the concerned shipping company in a timely manner. Many leading classification societies and few independent bodies have this skill and provide this service keeping in mind following factors.

- The diversity of the ship types under management. This can create a huge complexity in any ship management’s operations in formulating MRV process.

- The reliability of IT systems used in handling fuel data and other relevant information. A robust IT system will make it easier to capture and analyze data quickly and avoid errors.

- The existence of an environmental or a quality management system such as ISO 14001 and ISO 9001.

- The organizational structure of company, its energy policy and how it integrates MRV process into the business.

- The compliance review process based on interviews, document reviews, observation of systems and processes and corroboration of information.

Mr. Prakhar Singh Chandel,Corporate Fleet Manager (Energy Efficiency),Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement.

Corporate Fleet Manager (Energy Efficiency),Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement.

Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement.

About the Author:

Mr. Prakhar had an exciting sea career from 1989 to 2001, where in 2001, he stepped forward from the shoes of a Chief Engineer to a powerful Manager heading various Ship Management divisions. Starting as a Ship Surveyor with a classification society, he joined Bernhard Schulte Ship Management as a Technical Superintendent. Thereafter, a Senior Superintendent and a Fleet Manager with successful execution of various dry dock projects around the globe. As a Corporate Fleet Manager for Energy Efficiency in BSM, he is well qualified in QHSE management and trained many Masters and Engineers at BSM training centre. A Class certified auditor, Mr. Prakhar, is heading Energy efficiency projects for BSM group which has more than 350 vessels.

Mr. Prakhar had an exciting sea career from 1989 to 2001, where in 2001, he stepped forward from the shoes of a Chief Engineer to a powerful Manager heading various Ship Management divisions. Starting as a Ship Surveyor with a classification society, he joined Bernhard Schulte Ship Management as a Technical Superintendent. Thereafter, a Senior Superintendent and a Fleet Manager with successful execution of various dry dock projects around the globe. As a Corporate Fleet Manager for Energy Efficiency in BSM, he is well qualified in QHSE management and trained many Masters and Engineers at BSM training centre. A Class certified auditor, Mr. Prakhar, is heading Energy efficiency projects for BSM group which has more than 350 vessels.

Please Feel Free to Download the VEEMS (Viswa Energy Efficiency Management System) Architecture and Supplement below: